Co-designing Spaces for Care

Written by Leah Heiss

Associate Professor Leah Heiss, Dr Gretchen Coombs and Dr Troy McGee

Monash University Design Health Collab, Melbourne, Australia

How might we co-design spaces for care with those who provide and those who receive care? And could the process of inviting equal participation help us to evolve systems and spaces for care that are clinically, experientially, emotionally and sensorially more healing?

These questions have been driving our research for many years. They have propelled our interest in developing co-design approaches that enable those who are giving and those who are receiving care to have equal voices in the design of healthcare spaces and systems. This work has been embodied in a co-design method first developed in 2017, called the Tactile Tools co-design method, that has been used with hundreds of clinicians, consumers and stakeholders to map complex journeys of care (Heiss and Kokshagina, 2021). The contexts we work in are challenging and emotionally charged – spaces like acquired brain injury, cancer care, voluntary assisted dying, end-of-life experience (Heiss, Bush and Foley, 2020) and maternal disadvantage. Many of these contexts come with ingrained power differentials.

The Tactile Tools toolkit, iterated over many years, comprises acrylic ‘tiles’ in different shapes and colours that represent elements of the healthcare journey, including goals, roadblocks, workarounds, stakeholders and moments of empathy. The other key component of the method are personas that are co-designed with healthcare experts and that tell the stories of individuals seeking care and give context to their health care needs. In workshop settings, interdisciplinary teams work together to ‘map’ the journey of care for a person, and in the process highlight the barriers these individuals might face when seeking care. The haptic qualities of the toolkit (or ‘affordances’ in design lingo) enable clinicians, consumers, family members and other stakeholders to contribute to evolving new care pathways.

Figure 1: The Tactile Tools toolkit with persona, and tiles that represent goals, roadblocks, workarounds, stakeholders, empathy and pathways. Photographer: Adam R. Thomas, 2019.

Until 2020 these collaborative workshops occurred in face-to-face contexts, supported by the design tools. However, given the chaos of COVID we were faced with the challenge of shifting our work online, in a way that still engaged participants to empathise with the lived experience of people as they navigated care journeys.

In 2021 we started working with a visionary group of psychiatrists and psychologists at a large tertiary hospital in Melbourne, who were charged with designing a new residential treatment centre for people living with eating disorders. Rather than the traditional approach of designing healthcare facilities in Australia that involves a measured amount of community consultation by the architects with ‘patient representatives,’ the hospital was committed to co-designing not just the building but also the model of care that drove care delivery.

To clarify, a ‘model of care’ is essentially the way care is delivered, from the care provider to the patient or cohort. A model of care should be co-designed with constituents but oftentimes can be largely clinician driven. In the case of the hospital team, they were keen to co-design the model of care with as many stakeholders as possible, to ensure that it reflected the true needs of all who would receive or deliver care in the new centre.

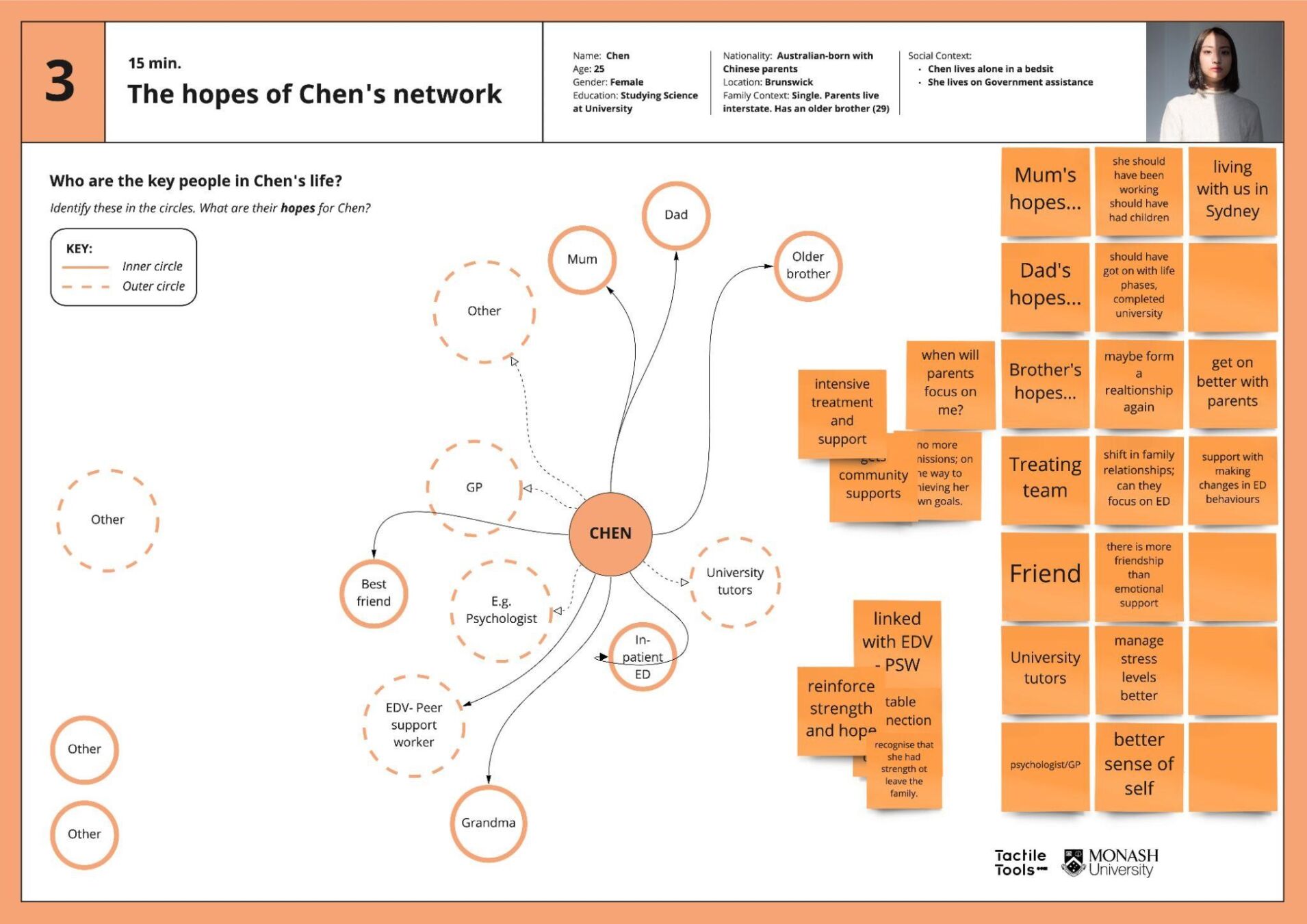

To enable this work, the Design Health Collab evolved our Tactile Tools Digital Toolkit (Heiss et al, 2021) to invite participation from across the sector to the design of the model of care for residential treatment of eating disorders. Over 35 lived experience advocates, carers, clinicians, sector advocates and government representatives worked in small groups to understand the experience of a future participant in the program: Stella, Demi, Emma, Daniel or Chen. The personas told the stories of individuals with a range of eating disorder experiences and were co-created with experts from the hospital team and lived experience advocates.

Through this first workshop participants collectively generated insights about the experience of receiving care from the perspective of the person with an eating disorder. This included how people would enter the program, what the key features of a program would be and how participants would ‘step down’ into community care. The thoughts and ideas of the whole group informed the creation of six principles to guide the delivery of care in the centre.

Figure 2: A Miro board from the Model of Care workshop in which participants collectively mapped the network of the persona Chen.

Given the co-designed Model of Care principles, it was critical that these inform the architectural planning processes. As I alluded to above, the creation of the functional brief by architects of health facilities often only comprises a small amount of community consultation. This might be with patient representatives who are selected for their enthusiasm, interest in participating, or alignment to the values of the organisation. Whether or not they are representative of the entire cohort is definitely less clear.

In the case of the Residential Eating Disorders Centre, the hospital was committed to really hearing the thoughts and ideas of people from across the entire ecosystem. As designers it was our responsibility to build a toolkit to enable people to participate in architectural conversations, whether they had any training or not.

We evolved the Tactile Tools Spatial Translations toolkit to interrogate how the previously co-designed model of care principles might be embedded within the architecture and design of the new centre, and to identify spatial, structural, sensory and experiential qualities that would support recovery and overall healing. The workshop brought back together the more than 35 stakeholders to discuss how spaces and architectures might be created to foster wellbeing and recovery for future residents in the centre. It also provided actionable design insights for the functional brief and provided support for the appointed architects in their design process.

Figure 3: An illustration from the Spatial Translations Miro board that helped to highlight key experiences prior to and during arrival at the centre. Illustration by Hatoun Ibrahim2022.

Through this ongoing co-design process we aim to amplify the voices of people who seek healing in the new centre. The work has ensured the lived experience of those who need care is integrated into architectural planning processes, helping to drive the creation of spaces for recovery.

References

- Heiss, L., M. Bush and M. Foley. (2020). One Good Death: Tactile, Haptic and Empathetic Co-Design for End-of-Life Experience. In L. Hjorth, A. de Souza e Silva & K. Lanson (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Mobile Media Art (pp. 493-505). Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Heiss, L., O. Hamilton, G. Coombs, R. De Souza and M. Foley. (2021). Mutuality as a Foundation for Co-designing Health Futures. In the proceedings of IASDR 2021 5-9 December 2021.

- Heiss, L and O. Kokshagina. (2021). Tactile co-design tools for complex interdisciplinary problem exploration in healthcare settings. Design Studies, 75. doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2021.101030

Leah Heiss

I am a Melbourne-based designer and RMIT researcher working at the nexus of design, health, and technology. My practice traverses device, service and experience and my process is deeply collaborative, working with experts from nanotechnology, engineering and health services through to manufacturing. My health technology projects include jewellery to administer insulin through the skin for diabetics; biosignal sensing emergency jewellery; and swallowable devices to detect disease. I designed Facett, the world’s first self-fit modular hearing aid for profit-for-purpose company Blamey Saunders hears. The design process for Facett has been acquired into the Museums Victoria heritage collection and been exhibited globally. Facett has received many accolades including the 2018 Australian Good Design Award of the Year, the 2018 CSIRO Design Innovation Award, the Premier’s Design Award 2018 (Product Design), 3 Victorian Government iAwards and Melbourne Design Award.